The 10 Most (Potentially) Inspiring Cases of Hacktivism

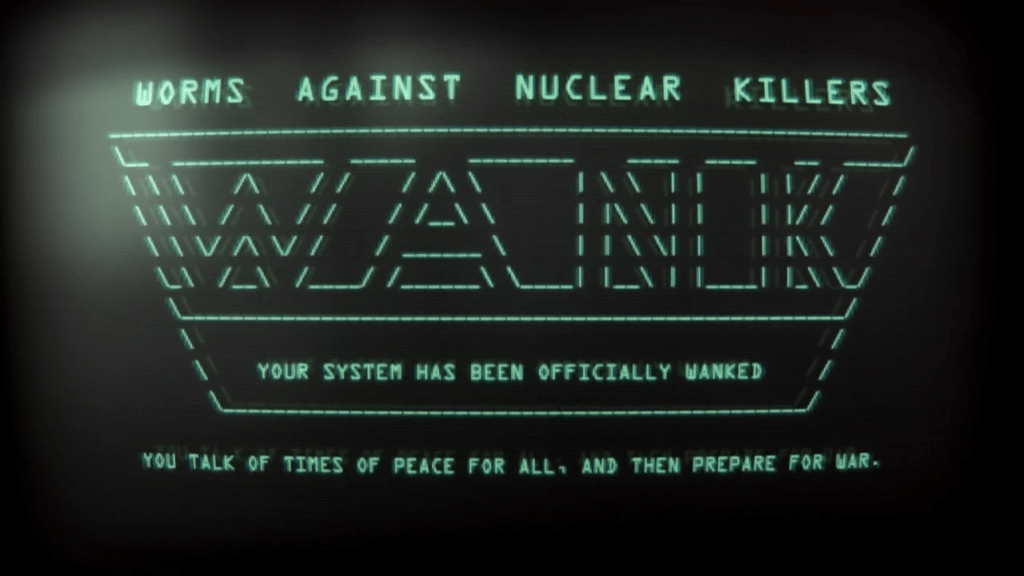

10) Worms Against Nuclear Killers (WANK)

There were earlier cases of hacktivism-like acts before the WANK Worm appeared — for instance, in 1971, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak developed a phone hack that allowed people to receive free long distance calls —- but this 1989 hack was among the first to provide a clear political bent, an attribute that would later help define the term. (At the time, the term “hacktivism” hadn’t yet been coined.) Developed by Australian hackers under the aliases of Electron and Phoenix, the worm was sent to a computer network shared by the U.S. Department of Energy and NASA, just one day before the launch of the Galileo spacecraft. So, why “Worms Against Nuclear Killers”? At the time, public concern over the Challenger shuttle disaster remained strong, and anti-NASA protestors argued that, should the Galileo crash like the Challenger, its plutonium-based modules would cause catastrophic destruction on falling to back to earth. Of course, the fear turned out to be unwarranted, but the message was clear: with the advent of the digital age, a radical new form of vigilante justice was possible, and no institutions — including governments — could expect to be exempt.

9) Kosovo Hacktivism

The late 90s saw the rise of more concentrated and focused hacktivist efforts, perhaps none more influential than during the controversial conflict in Kosovo. As NATO collaborated in a devastating aerial bombardment of the region, hackers around the world launched DoS attacks (now a trademark hacktivist tactic) and defaced or hijacked websites to disrupt governmental operations. Team Sploit, an American group, hacked into the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority site, writing “Stop the War”; the Russian Hackers Union infiltrated the U.S. Navy site, writing “stop terrorist aggression against Jugoslavia on a US Navy site”; and the Serbian Crna Ruka carried out DoS attacks on NATO websites. Following the accidental bombing of a Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Chinese hacktivists joined the effort, too. While most of these actions were purely protest statements, a precedent was set for transnational hacktivist collaboration and the development of a larger hacktivist community.

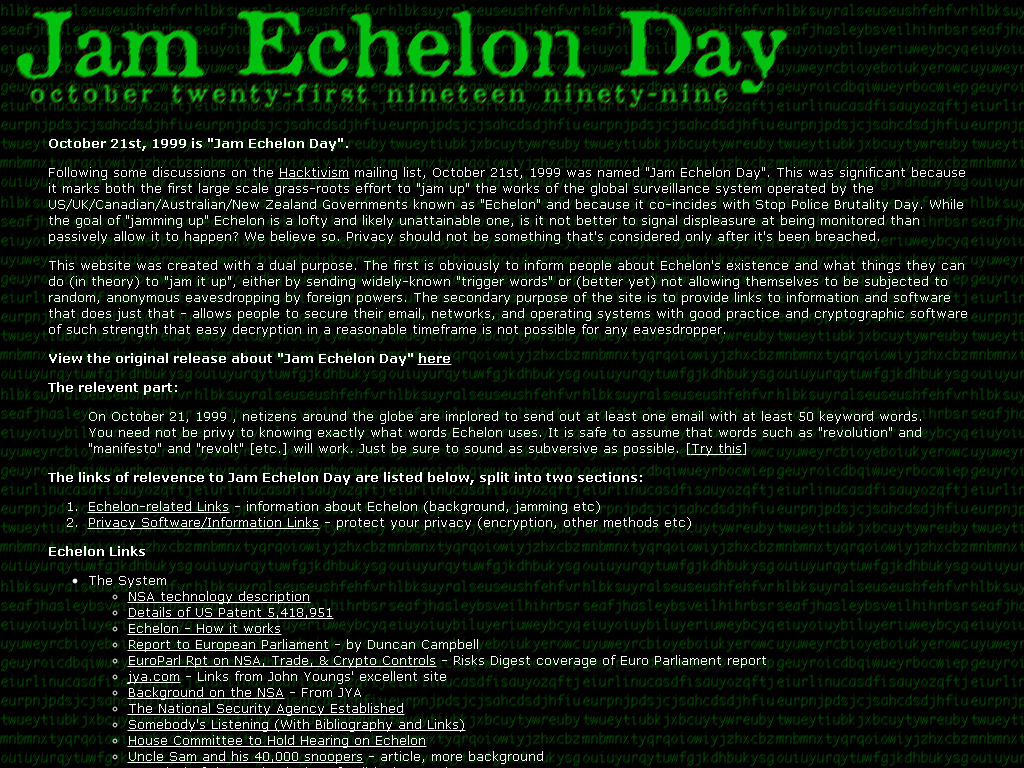

8) Jam Echelon Day

The same year of the Kosovo conflict, an email chain appeared with the following lede: “STAND UP FOR THE FREEDOM TO EXCHANGE INFORMATION!” Today, it’s a familiar rallying cry in the hacktivist community, but in October 1999 it carried revolutionary gravitas. Now known as Jam Echelon Day, hacktivists from around the globe coordinated to disrupt the ECHELON surveillance system, operated by the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and described by hacktivist leaders as “very real, very intrusive, and ultimately oppressive.” As part of the plan, participant “netizens” were instructed to send at least one email containing “subversive” keywords from a supplied list, which would trigger the ECHELON system and eventually overwhelm its computers. While limited in effectiveness, the most notable feature of Jam Echelon was its grass-roots, populist premise: “Now is a chance for anyone, regardless of computer expertise, to become an instant hacktivist.”

7) Anonymous Joins Occupy Wall Street

When word of planned protests on Wall Street started to spread in late Summer 2011, Anonymous was among the first major proponents. For a movement that was occasionally accused of disorganization, the hacker collective stood out for its unique ability to unify disparate factions, turning a NYC-centric event into a national and even international protest. In October, some members (controversially) hit the New York Stock Exchange website, but it’s main role remained as a political sponsor, proving for the first time that it could effect change through more traditional means when necessary; that the hacktivist community could organize and mobilize just as well as disrupt and attack; and that, again, when the circumstances called for it, Anonymous could move from behind their laptops and onto the streets.

6) Phineas Fisher Takes Down Gamma International

Don’t take it from me: Biella Coleman, a professor at McGill University in Montreal whose specialties are hackers, hacktivism, and Anonymous, claims that, “For politically minded hackers, Phineas is a legend already.” In January of 2017, Spanish authorities claimed to have arrested the mysterious hacktivist after an attack on the Catalan local police website, only for Fisher to appear on Twitter a few hours later, assuring followers that he/she was “alive and well.” Among the hacker’s many targets include FinFisher, Hacking Team, and the Turkish government, but the most famous raid came in 2014 when Fisher hacked Gamma International, a British-German spyware-maker, then dumped 40 gigabytes of data on Reddit, exposing the company for selling software to suppress Bahraini activists (a rumor that Gamma had long denied). Nor is Fisher interested in any kind of elitist self-promotion. Soon after the Gamma hack, he released a detailed how-to guide “to hopefully inform and inspire you.”

5) Anonymous Attack Scientology

Back in 2008, the majority of the public had never heard of Anonymous, a renegade offshoot of the online 4chan community. The loose affiliate had conducted a few petty attacks against internet rivals, but they could hardly be mistaken for supporting any coherent ideology, save perhaps free speech. Then Project Chanology was launched, and Anonymous — and hacktivism — were never the same. Following the Church of Scientology’s attempts to censor a controversial interview with Tom Cruise, by far the Church’s most famous member, Anonymous initiated a massive string of denial-of-service attacks, black faxes, and more. As the story gained attention in the media, Anonymous began to organize street protests across the world — from the Church’s headquarters in Clearwater, Florida, to Melbourne, Australia — sporting their now familiar Guy Fawkes masks, and calling on the government to investigate Scientology’s tax exempt status. Since then, numerous other exposés of Scientology have surfaced, and Anonymous has become a household hacktivist name.

4) Operation(s) Darknet

Concurrent with Anonymous’s foray into Occupy Wall Street, the group carried out a round of major hacks against dark web sites hosting child pornography. In October 2011, 1,600 usernames were unmasked from “Lolita City,” and forty other image-sharing sites were disabled altogether. A year later, Anonymous relaunched Operation Darknet, posting emails and IP addresses of suspected pedophiles on an online message board. Still, by far the largest takedown came in February 2017: in one fell swoop, a single Anon wiped out 20% of the dark web, at least half of which was child pornography material. As the hacker explained an interview with Newsweek, “I didn’t plan this attack, just had the right idea and took the opportunity after finding out what they were hosting.”

3) Hacktivists Strike ISIS

The largest Anonymous operation yet, Operation ISIS involves at least four of the collective’s splinter groups, including Binary Sec, VandaSec, CtrlSec, and GhostSec, the latter of which began in response to the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris. In addition to being Anonymous’s largest operation, OpISIS is widely assumed to be its most challenging, with many of participants said to be “spend[ing] a lot of time tracking people that can’t be found,” per the Director of the National Security Agency. Still, not all is in vain. Soon after the November 2015 Paris attacks, Anonymous claimed to have shut down over 5,000 pro-ISIS Twitter accounts. Since then, hackers have struck dozens of DDoS attacks against the terrorist organization and hijacked Twitter accounts. For his part, UK Security Minister John Hayes is publicly in favor of the hacktivists, telling the House of Commons that he’s “grateful for any of those who are engaged in the battle against this kind of wickedness.”

2) Hacktivism and The Arab Spring

When a series of local political protests began in Tunisia in December 2010, few could have predicted that they would lead to one of the most significant upheavals of the twenty-first century…and yet Anonymous took immediate interest. On January 2, Operation Tunisia began; by mid-month protests had swept across North Africa; by the end of the month Egyptians had gathered in Tahrir Square, demanding that President Hosni Mubarak resign. The Arab Spring was under way. As the first large-scale revolutionary movement to occur in the digital age, it was also perhaps the first in which information was the principal weapon: who had it, who controlled it, and who knew it. Unsurprisingly, international hacktivists realized the situation from the get-go and helped to restore government-suppressed web mirrors and proxies, allowing citizens to regain access to news sites and social media platforms. When servers went dark, groups like Anonymous and Telecomix set up ad hoc communications systems and dial-up modems. Meanwhile, massive cyber-attacks hit the governments of Tunisia, Egypt, and Syria, disrupting operations and disabling communication updates.

1) Aaron Swartz

Our most awe-inspiring case of hacktivism arguably isn’t really hacktivism, or at least not exclusively. While Aaron Swartz’s career included hacktivist initiatives, Swartz was much more: a committed entrepreneur, political organizer, programmer, and writer, among other occupations. He co-developed popular software and code, worked on the early stages of the Creative Commons, and founded Infogami, which he agreed to merge with Reddit in 2006. In 2008, Swartz founded the influential Watchdog.net, which tracks politicians, and created what’s now called SecureDrop, which operates a secure communication channel between journalists and whistleblower sources; today its clients include The Washington Post, The New Yorkers, The Guardian, and ProPublica. A strong believer in a free, open-access web, what would’ve been among Swartz’s great accomplishments was tragically one of his last: after attempting to download paywalled academic journals from JSTOR via MIT’s computer network, Swartz was caught and arrested. During the course of a highly controversial, protracted federal case, Swartz faced up to 13 charges. In January 2013, he committed suicide. Two days later, Anonymous hacked several websites to set up tributes. Despite his premature death, Swartz’s legacy and hacktivist spirit remains, especially in his push for open access and a better, more humane world wide web.